Born: September 10, 1873

Birthplace: Bradford, England

Died: October 25, 1948

Place of Burial: Lake View Cemetery, Jamestown, New York

Contribution: Suffrage leader and women’s rights activist

The world was in the throes of World War I when Jamestown, N.Y. resident Edith Ainge went to Washington, D.C. to join the national campaign for women’s right to vote. By the time the 19th Amendment was finally added to the Constitution in August 1920, she had risen to the inner circle of the movement’s newest group of leaders.

Born in England on Sept. 10, 1873, Edith came across the Atlantic with her mother, Susanna (Taylor), and then five siblings when she was nine years old in 1883. Father William Ely Ainge apparently made the journey earlier. After their arrival the family grew to include nine children total, with Edith being the second oldest.[1]

William soon made a name for himself in the bustling business world of the Gilded Age, serving as the accountant and business manager for a prominent steel company in Ohio. His ties to Jamestown began when he became affiliated with Art Metal, a Jamestown furniture company specializing in metal office furniture. In the 1910s, he opened his own accounting firm providing accounting services to corporate clients throughout the Northeast from dual offices in Jamestown and Youngstown, Ohio.[2] The family moved to the corner of Fourth and Pine Streets in downtown Jamestown, where William’s local office was located.[3]

Around this time Edith became active in the Women’s Political Union, a new suffrage organization founded downstate by Harriot Stanton Blatch (Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s daughter) that sent a field organizer to Jamestown in 1914.[4] Where earlier suffrage organizations had focused on petition campaigns and behind-the-scenes lobbying, the WPU took the suffrage campaign to mass audiences, using parades and street meetings to recruit working women and garner more publicity.

Edith quickly stepped up to chair the WPU’s Jamestown chapter.[5] In this role, she spearheaded local events promoting the passage of women’s suffrage in New York State. With the first statewide referendum on the issue slated for November 1915, the WPU orchestrated a torch relay across the state, from Long Island to Buffalo. As the “Liberty Torch” passed from town to town, rallies and speeches ensured maximum media coverage. On July 25, the torch made its way from Salamanca, N.Y. to Jamestown, with Edith coordinating its arrival. A week full of events ensued around Chautauqua County, including speeches by Blatch and others at the Celoron, N.Y. bandstand, a boat tour of towns around Chautauqua Lake, and a highbrow “garden party” in Jamestown. On Thursday, Blatch spoke at the nearby Chautauqua Assembly. Afterward, the women motored the torch into the northern half of the county, through the quaint towns of Westfield and Brocton, en route to street meetings in Fredonia and Dunkirk and, finally, Buffalo.[6]

Although voters in Ainge’s home county of Chautauqua were in favor, the referendum failed to pass that year statewide. But the movement’s leaders were not easily shaken. Women across the state doubled their efforts. Their work paid off in 1917 when New York became the first state east of the Mississippi to grant women the vote.

Edith’s attention, meanwhile, turned toward the bigger challenge. In the summer of 1917, she headed to Washington to take part in demonstrations being coordinated by the National Woman’s Party.[7] The WPU had merged with this new organization the previous year to funnel its activities toward a national constitutional amendment. Led by Alice Paul, a young Quaker woman who had become involved in the suffrage cause while studying in England, the NWP organized pickets outside the White House gates beginning in January 1917.

The “Silent Sentinels,” as they were called, didn’t utter a word; by holding up their colorful banners at the nation’s seat of power they aimed to pressure President Woodrow Wilson and congressional leaders into bringing a suffrage amendment to the floor of Congress for debate. But events in Europe soon enveloped their silent protests in controversy. Angry locals swarmed the women in August when the Sentinels appeared with a banner that compared President Wilson to the German kaiser. Women were knocked down and assaulted as the crowd tore at their banners. A shot was fired into the NWP headquarters across the street. Thereafter, arrests became commonplace – but not of the assailing mob. Instead, police targeted the women on the picket line.[8]

On September 4, the day of Ainge’s first arrest, crowds had gathered downtown for a different spectacle. A “gala” parade was planned to send off the first group of draftees headed for Europe. As President Wilson arrived and the festivities got underway, a group of NWP women took positions by the parade reviewing stand. Edith was at the front of the line, carrying a banner that read: “It is unjust, Mr. President, to deny women a voice in their own government while the government is conscripting their sons.” NWP member Dorothy Stevens described what happened next:

“They were gathered in and swept away by the police like common street criminals – their golden banners scarcely flung to the breeze.”[9]

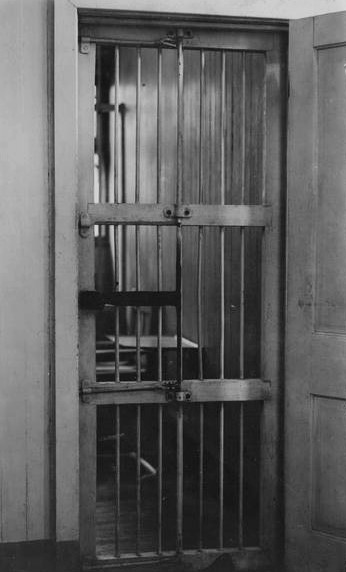

Ainge was one of 12 women arrested that day. According to a newspaper account, she and another woman attempted to give “suffrage speeches” in court, but the judge quickly stopped them and gave a mini-speech of his own; American women would never win the right to vote with such tactics, he said. He sentenced them to 60 days in the Occoquan Workhouse, a women’s prison located nearby in Virginia.[10]

Some of Edith’s neighbors undoubtedly shared the judge’s disapproval. An editorial appearing in the Jamestown Evening Journal on Sept. 7 called the picketing a “disgraceful” attempt to “annoy the president during this his time of great trial.” The editor continued, “Miss Ainge is naturally too intelligent a woman to get mixed up in this militant movement. . . . She is a woman of unusual energy and independence from whom it is reasonable to expect better service. . . . While her friends may have some sympathy for Miss Ainge, they will have none whatever for her acts.”[11]

Edith now began a great trial as a political prisoner. A legal affidavit that she prepared following her release attests to the poor conditions she and other women endured while incarcerated at the workhouse. Long hours in the sewing room were broken up by only one half-hour break in the middle of the day. Much of the food was wormy and rancid, making it “impossible” to eat. Some women fell ill but were denied medical treatment. Near the end of her sentence, Edith required temporary hospitalization. When she refused to return to work she was sent to the district jail in Washington to serve her final two weeks in solitary confinement. “I was in perfect health at the time I was sent to Occoquan,” she stated, “and . . . at the end of six weeks, I had lost 23 pounds and was unable to walk from lack of nourishment.”[12]

On the day when Edith was released in November, Alice Paul and another NWP prisoner, Rose Winslow, were taken on stretchers to the prison hospital. While there they resolved to begin a hunger strike.[13]

Although Ainge did not experience the multiple hunger strikes that followed, she might very well have participated had she been in prison still. Before she was released, she helped to circulate a powerful statement of protest from inside the walls of her cell. She and 10 other occupants of solitary confinement began pushing a folded up piece of paper through the tiny space surrounding pipes in the walls. In it they declared:

“As political prisoners, we, the undersigned, refuse to work while in prison. We have taken this stand as a matter of principle. . . . This action is a necessary protest against an unjust sentence. . . . We were exercising the right of peaceful petition, guaranteed by the Constitution of the United States. . . .”[14]

In the months afterward, Edith was arrested four more times, although her other sentences amounted to a few days total.[15] By 1918, after reports of the women’s mistreatment had won them sympathetic headlines, the Wilson administration was reluctant to give Paul and her followers the media attention that longer sentences might bring.

In January 1919, with the proposed amendment still held up in the U.S. Senate, Ainge lit the first of the symbolic fires used in the NWP’s Watchfire Demonstrations. Taking position, once again, in front of the White House, the women lit a fire in an urn and proceeded to toss copies of President Wilson’s speeches into the flames.[16] NWP member Doris Stevens later claimed, “A soldier rushed to the scene with a bucket of water to extinguish the flames, but the fire continued to burn as if by magic. A policeman used a fire extinguisher, but the fire burned on. The flames were as indomitable as the women who guarded them. Rain came, but all through the night the watchfire burned. All through the night the women stood guard.”[17]

Later that year, after the Senate had voted down the amendment, Ainge signed on to the NWP’s “Prison Special” tour. On Feb. 15, the 26 women went to Union Station in Washington and boarded a train they christened “Democracy Limited.” Over the course of the next three weeks, they spoke of their prison experiences in cities across the country, from New Orleans to San Antonio and Los Angeles and New York, with many stops in between. They appeared before crowds in prison garb to accentuate their message about the injustice of their arrests.[18]

When the Senate finally approved the Amendment in June of 1919, it was off to the states for ratification. Edith remained active in the cause as it made its way through state conventions. The 1920 census recorded her employment in “Suffragist Organizing.”[19]

In fact, her work on behalf of women’s rights did not end with the amendment’s adoption. Ainge was elected treasurer of the NWP in 1922 and continued to serve on the organization’s National Council until at least 1930.[20] As part of the inner circle, she helped promote what is known today as the Equal Rights Amendment. Proposed by Alice Paul in 1923, the amendment sought to eliminate the full slate of legal barriers that still discriminated against women in the home, in the workplace, and in society at large. Edith was among a large delegation of women to advocate for the amendment with President Calvin Coolidge directly in 1923. They were received in the East Room of the White House. When Coolidge was re-elected for a second term, she and a dozen other NWP women talked up the amendment to crowds gathered for the inauguration, planting themselves at the capital’s six busiest street corners the night before the event.[21]

Like her mentor, Alice Paul, Ainge’s interest in women’s rights extended beyond America’s borders, as well. In 1930, she and seven other women from New York State — including her younger sister, Jessie Ainge — gained an audience with President Herbert Hoover regarding a proposed international provision giving women equal nationality rights with men. The issue was then being considered by an international law conference at the Hague.[22]

Although travels likely took her away much of the time, Ainge continued to make her home in Jamestown into the 1930s.[23] The 1940s found her living with siblings at a home in Angola, N.Y., where she also entertained Alice Paul on more than one occasion. Even as she aged, Edith maintained a close friendship with Paul. Their letters speak of visits they traded to each other’s homes and Edith’s support of Paul’s ongoing activism.[24]

When Edith passed away in 1948, her death was noted in the New York Times. Paul traveled from Washington to attend the funeral services in Buffalo and Jamestown. Edith was laid to rest in Jamestown’s Lake View Cemetery, alongside her parents and six of her siblings. Her gravestone bears the simple words: “Edith M. Ainge, 1873-1948, Suffrage Leader.” [25]

Ainge’s legacy is also memorialized on a historical marker in downtown Jamestown. Erected on September 4, 2020 with funds from the City of Jamestown, the marker is located at the corner of Fourth and Pine streets, where Edith was living during the pivotal years of her suffrage activism.[26]

Compiled by Traci I. Langworthy, 2020

Primary Sources to Explore

“Torch is Now in Jamestown” from The Buffalo Express, July 27, 1915

“Miss Ainge Has Gone to Jail” from the Jamestown Evening Journal, September 7, 1917

“Jamestown Woman in Jail,” an editorial appearing in the Jamestown Evening Journal, September 7, 1917.

Affidavit of Edith Ainge (1917) from the records of the National Woman’s Party at the Library of Congress

Account of the Watchfire Demonstrations by Doris Stevens (1920)

“Suffragists Have Modern Betsy Ross” from The Binghamton Press, July 18, 1919

“Cite 50 Ways Laws Hold Women to Be Inferior” from The New York Times, March 2, 1924

“Women to Urge Equal Rights on Inaugural Eve” from Chicago Daily Tribune, March 1, 1925

References

[1] John P. Downs, ed., History of Chautauqua County, New York, and its People (New York: American Historical Society, Inc., 1921), 3: 581; “Miss Edith Mary Ainge, Noted Suffragette, Dies,” Buffalo Evening News, October 27, 1948, 64; Passenger Lists, 1865-1935, Library and Archives Canada, Series RG 76-C, Roll C-4532, Ancestry.com.

[2] Downs, History of Chautauqua County…, 3: 581; Jos. G. Butler, Jr., History of Youngstown and the Mahoning Valley, Ohio (Chicago: American Historical Society, 1921), 2: 300, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433081822698.

[3] United States Federal Census, 1910, Jamestown Ward 1, Chautauqua County, New York, Roll T624 930, Page 4A, Enumeration District 144, Ancestry.com; The Journal’s Directory of Jamestown, 1909-1910 (Jamestown: Journal Printing Company), 2-3, https://www.prendergastlibrary.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/JTN1909-10_WEB.pdf, accessed August 20, 2020.

[4] “Miss Edith Mary Ainge, Noted Suffragette, Dies,” Buffalo Evening News, October 27, 1948, 64; Downs, History of Chautauqua County, 1:351.

[5] The Journal’s Directory of Jamestown, 1915-1916 (Jamestown: Journal Printing Company), xxiii, https://www.prendergastlibrary.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/JTN1915-16_WEB.pdf, accessed August 20, 2020.

[6] “Torch Is Now in Jamestown,” The Buffalo Express, July 27, 1915, 2; “Women On Way to City With Torch,” Buffalo Courier, July 27, 1915.

[7] “Miss Ainge Has Gone to Jail,” Jamestown Evening Journal, September 7, 1917, 2.

[8] Doris Stevens, Jailed for Freedom (New York: Boni and Liveright, Inc., 1920), http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:GSE.LIBR:454096, accessed August 20, 2020.

[9] Stevens, Jailed for Freedom, 139.

[10] “Edith Ainge Sent to Jail,” Jamestown Morning Post, September 7, 1917, 12; “Miss Ainge Has Gone to Jail,” Jamestown Evening Journal, September 7, 1917, 2.

[11] “Jamestown Woman in Jail,” Jamestown Evening Journal, September 7, 1917, 3.

[12] Affidavit of Edith Ainge, 16 November 1917, Group 1, Correspondence (1891-1940), National Woman’s Party Records, MSS34355, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[13] Stevens, Jailed for Freedom, 216-217.

[14] Stevens, Jailed for Freedom, 177-178.

[15] Stevens, Jailed for Freedom, 354.

[16] “Detailed Chronology: National Woman’s Party History,” Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman’s Party, Library of Congress, American Memory, https://www.loc.gov/static/collections/women-of-protest/images/detchron.pdf, accessed August 12, 2020; “Watchfires of Freedom” in Shall Not Be Denied: Women Fight for the Vote, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/exhibitions/women-fight-for-the-vote/about-this-exhibition/hear-us-roar-victory-1918-and-beyond/house-and-senate-passage-leads-an-exhausting-ratification-campaign/watchfires-of-freedom/, accessed August 12, 2020; Stevens, Jailed for Freedom, 305-313.

[17] Stevens, Jailed for Freedom, 305-306.

[18] “Detailed Chronology: National Woman’s Party History,” 20-21.

[19] “Suffragists Have Modern Betsy Ross,” The Binghamton Press, July 19, 1919, 17; United States Federal Census, 1920, Jamestown Ward 1, Chautauqua County, New York, Roll T625 1091, Page 4A, Enumeration District 148, Ancestry.com.

[20] “Woman’s Party Meeting: Mrs. Belmont Completes $146,000 Gift for Headquarters,” New York Times, June 23, 1922, 9; “Adopt a Program for ‘Equal Rights,’” New York Times, December 8, 1929, 26.

[21] “Women Open Fight for Equal Rights,” New York Times, July 21, 1923, 8; “Plan Equal Rights Fight,” New York Times, November 5, 1923, 15; “Coolidge Assures Women of Victory,” New York Times, November 18, 1923, 22; “Cite 50 Ways Laws Hold Women to Be Inferior,” New York Times, March 2, 1924, 29; “Women to Urge Equal Rights on Inaugural Eve: Plan Soapbox Attack on Washington,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 1, 1925, 5.

[22] “Adopt a Program for ‘Equal Rights,’” New York Times, December 8, 1929, 26; “Women Protest Ban at the Hague,” New York Times, April 10, 1930, 7.

[23] United States Federal Census, 1930, Jamestown Ward 3, Chautauqua County, New York, Page 9B, Enumeration District 62, Ancestry.com; Polk’s Jamestown City Directory, 1937-1938 (Pittsburgh: R. L. Polk and Company, 1938), 25.

[24] United States Federal Census, 1940, Angola, Town of Evans, Erie County, New York, Roll m-t0627-02528, Page 9A, Enumeration District 15-74, Ancestry.com; Edith Ainge Correspondence, 1942-1944, fol. 36, Series I, Alice Paul Papers, MC 399, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:RAD.SCHL:29994517, accessed August 12, 2020.

[25] “Miss Edith Ainge,” New York Times, October 26, 1948, 31; “Miss Edith Mary Ainge, Noted Suffragette, Dies,” Buffalo Evening News, October 27, 1948, 64; “Miss Alice Paul, World Party Head, Meets Local Group,” Buffalo Evening News, October 28, 1948, 39; Edith M. Ainge, grave marker, Lake View Cemetery, Jamestown, Chautauqua County, New York.

[26] Dennis Phillips, “Committee Honors Women’s Rights Leader,” The [Jamestown] Post-Journal, September 5, 2020, D1, https://www.post-journal.com/news/local-news/2020/09/committee-honors-womens-rights-leader/, accessed September 7, 2020.